The environment we live in is not static in nature. Conditions around us are ever changing, constantly placing new demands on our bodies and minds. The stress/recovery/adaption cycle (or SRA cycle as I’ll refer to it here) is a mechanism used by virtually all living creatures on the planet to ensure optimal existence and survival, the most vital form of “rolling with the changes.”

The SRA cycle is composed of a series of physiological operations that occur from a macro-view of entire bodily systems down to the microscopic cellular level. You or I could write an entire book on the details of these events if given the appropriate time, resources, and level of interest (and many have been written – none lacking thickness or density), but I will spare most of the specifics for the sake of keeping the information in this post wrapped up in a “here’s what you need to know and understand how it relates to training” nutshell. Let me begin by providing a basic real-world example of the SRA cycle at work.

Let’s say that you need to do some landscaping – and not just spraying weeds – the hard kind that requires copious amounts of digging that you never seem quite prepared for. Due to the normal absence of digging needs in your life (you’ve never needed a shovel at the office), this sudden activity produces a stimulus, most notably present on your hands in the form of blisters. You decide to wait until the sun goes down to pop these blisters (like any good proponent of Hoosier folklore) and peel off the dead skin, revealing a layer of a little more rigid skin underneath. This new rigid skin grows over and voila! You’re ready to shovel away pain-free again. And after you do, no more blisters! And unless you spend a considerably greater amount of time digging next go-round, the blisters will probably never come back.

Now this is a very simple example that most of us have experienced at some point, but breaking it down depicts the basic premise of the SRA cycle: the use of the shovel produced a stress in the form of blisters, the body took time to recover from that stress, and ultimately produced an adaptation of the skin so that you’d be prepared for a repeated bout of that stress.

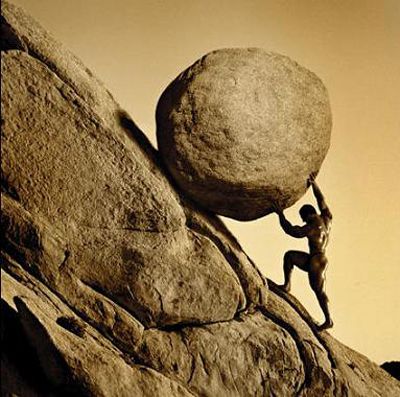

Below is a more visual outline of the SRA cycle at work. As you can see, each time a stress is introduced, it is followed by a period of recovery and subsequent adaptation, creating a new “baseline” level. Further adaptation requires a stress greater than this new baseline.

As I mentioned, the SRA cycle occurs as a result of many different stimuli, and the process is set in motion any time we are met with a stress. Hopefully this includes any time we step foot in the gym. The first step in making any desired physical change through training is to introduce appropriate stress during each workout.

Stress

For most people with any training experience, the concept of feeling “stress” during a workout probably sounds familiar. If you are in this boat, you can likely remember certain workouts that felt particularly “stressful,” probably the ones that leave you gasping for air while laying in a pool of your own sweat and/or tears. Now I won’t argue that workouts of this kind don’t provide stress, but I’d like to make some distinctions here when we talk about overall stress vs. training-specific stress.

As is often the case, let’s keep things specific to your goals. First off, let’s imagine you are wanting to increase your upper body strength (and you have some realistic metrics for that). Now, you go into the gym every day with the mindset that whatever you do needs to be extremely challenging, or in a more popular term, “suck.” So you delve into anything and everything conditioning, since that’s what most people go to when they think of workouts that suck. An endless chain of interval training, long-distance running, and anything creative in between constantly leaves you drifting in that ocean of sweat and tears (and now possibly vomit) that I mentioned earlier. At this rate, it’s pretty safe to say that these workouts will induce plenty of stress needed for adaptation and then some. However, what adaptation is this stress building toward? It’s very likely that these workouts will induce stress necessary to lose some body fat and improve muscular endurance and cardiorespiratory efficiency, but at the end of the month your upper body strength still isn’t up to par.

Providing stress in the form of dedicated strength work in this case is more specific to your goal and thus should be used to drive strength adaptations. Utilizing workouts in which you use compound upper body exercises and gradually increase the load and/or volume would supply a more specific stress in this case. And the same could be said vice versa. If your goal is to improve your conditioning, then maxing out on the bench press all the time probably won’t be a good use of your time either. I also want to be clear here that I’m not saying you should never vary training or that you can’t make some adaptations simultaneously, only that you should always keep in mind how your training stress relates to your desired adaptation.

Remember the earlier blister example? Why is it that you could potentially form blisters again if you went out and dug holes for 3 hours instead of 1? In short, because your body only adapted to the first imposed stress: 1 hour. Wielding a shovel for 3 hours is a much larger stressor, and your body must repeat the SRA cycle again in order to adapt to it. It is imperative that you keep this in mind for training in the long-term perspective. In order to progress continually, you must incrementally introduce larger magnitudes of stress to trigger greater adaptations. As a beginner, this is a much easier endeavor, as the level of stress needed is relatively small. As you become more advanced, you simply have to do more work since your “baseline” adaptation level is much higher. Often this is accomplished through accumulating stress.

Cumulative stress refers to the effect of using a combined stress from a series of workouts, instead of relying on stress from a single workout, to drive adaptation. This is a consideration for more intermediate or advanced individuals, who have heightened their baselines. Since beginners need only a small amount of stress (and can’t physically induce the same high levels of stress), they are fine keeping their focus day to day. How do you know when you aren’t a beginner anymore? Simply when you can no longer progress workout to workout. This basically shows that your SRA cycle has lengthened and you now must rely on more cumulative stress. In this case you need to start thinking more about how much work you accumulate in a week or month than what you do in a single workout.

The characteristic of accumulating stress also drags in the issue of what I’ll call “junk stress.” It’s important to keep in mind that all stress from training accumulates and can have a systemic effect on performance. For example, if you’re running a 5k on Saturday and you choose to also start a high-frequency squat program that week, you aren’t training optimally for the 5k. Your legs will accumulate a lot of stress through the week and come Saturday, may still not be recovered. And even if they aren’t killing you on Saturday, maximal lower body strength has very little to do specifically with running an endurance-based race anyway. You would be better off just waiting to start the squat program after the 5k and save yourself the junk stress that will likely hinder your performance.

Recovery

During a workout, we tend to focus only on what is happening at the moment, sometimes leading us to believe that it is only what goes on in the gym that has an impact on our progress. However, things are a bit more complex than that, no matter how productive you feel that your workout was or how much you feel you (dare I say) “killed it.”

Be sure to look at the training process through a fairly wide lens. In terms of the SRA cycle, any individual workout itself only comprises the stress portion. When the workout has ended, it is essential that we continue to be mindful of recovery so that we may adapt optimally. Rarely do changes happen in an instant, and meticulous physiological events are no exception. Adequate recovery time is necessary so that adjustments can be made to specifications. Think of it like this: any muscle you’re wanting to build? It’s all constructed outside of the gym. Your workout simply provides the stress that draws up the blueprint. Adhering to the demands of this blueprint by recovering properly involves two main factors: nutrition and sleep.

I could (and probably will eventually) write an entire post discussing specifics of nutritional needs for different goals. I will spare the word count for the sake of this post and put it as simply as I can: eat in accordance to your training goal. If you are trying to lose body fat, make sure you are in a caloric deficit, but not a deficit so extreme that you can hardly make it through your workouts. Likewise, if you are trying to gain muscle, you need to consume the necessary amounts of calories and protein to support that. When it comes down to it, you’re dealing with energy expenditure and consumption. At least realize that what you eat covers half of that equation. This is admittedly a huge oversimplification, so if you’re looking for details in the form of caloric and macronutrient recommendations, you can either bug me until I write a post containing them… or just email me.

My discussion of sleep’s role in recovery is going to be even more elementary. In fact, I can sum it up with a few bullet points:

- Sleep is important and we all need it to survive.

- More bodily tissue remodeling and hormonal change happens during sleep than any other time, making sleep even more important for those who train.

- The more stress you apply through training, the more sleep you will need.

There you go, folks. Most of you have been sleeping your whole lives, so I won’t try to provide an instruction manual on subject. However, many still neglect sleep and then wonder why they start spinning their wheels and rolling downhill.

If you want to utilize any other means for recovery like massage or meditation or anything of the sort, go ahead. I can’t speak for everything out there, but if you feel that it truly helps you feel better, then maybe it will aid in recovery. But as for what there is established evidence for, nothing has a measurably significant impact on recovery compared to nutrition and sleep. If you prioritize training, prioritize them as well.

Adaptation

Finally we get to the golden goose of the SRA cycle: the resulting adaptation. Adaptation in the long term is usually representative of a specific goal and is essentially the reason why we train. In the short term though, adaptation often only represents a new baseline. This is an important concept, as being able to realize that you’ve hit a new training baseline can make the difference between continuing progress and hitting a big ugly road block.

Recall the basic premise of the SRA cycle – that you must provide an appropriate stress require recovery and stimulate the according adaptation. This means that once you’ve made adaptations to a certain degree, what used to be an appropriate stress just isn’t enough anymore. For instance, doing the same bench press workout with sets of 5 at 225 lbs. may have done the trick for getting your bench press to 250, but likely won’t be the key for getting your bench to 300, even if you add more sets. In this case, adding intensity by adding weight to the bar would be a primary way of adding stress sufficient to surpass your new baseline. Because of this principle, we must always be mindful that in order to progress long-term, it is crucial that we are continually adding larger stresses relative to our current adaptations.

The act of keeping adaptation in check can vary in difficulty depending on training experience. Beginners have a pretty easy time keeping tabs on the process, mostly because the stress they incur is relatively small, so the entire SRA cycle runs its course in an accordingly small time frame, often within a couple days. Similarly, more advanced trainees need larger stresses and thus longer SRA cycles. This usually means that training stress must be accumulated through a series of workouts, until it finally provides the cumulative stress to push past the much higher adaptive baseline. This is also why (when you do the math) you can witness beginners increase a lift by 5% in one week, while an advanced lifter may have to train for 12 to 16 weeks to attain the same 5% improvement.

Speaking of accumulating stress – an important note to make here: if you’re an advanced trainee, be sure to know that inducing large amounts of training stress repetitively also induces large amounts of fatigue. Because of this, it is not uncommon for long training cycles to give the periodic appearance that you are not progressing. Always keep in mind that this fatigue masks the ability to express the true adaptation-in-process. This is a key reason for deloading periods, or in the case of competitors, tapering for competition. This is a topic that I’ll get into in a little more detail soon – stay tuned.

Recap

I’ll conclude with a simple review of how to use the SRA cycle to govern your training:

- Make sure that your workouts produce a stress specific to your goals. The magnitude of this stress should gradually increase as you become more adapted.

- Allow adequate time between workouts for recovery. This time frame can vary based on your experience level and the nature of the workouts themselves. Maximize recovery through food and sleep.

- Be mindful as to what stresses you have adapted to and where your new baselines are. This will ensure that you are manipulating your workouts correctly for long-term progress and not just wasting time in the gym.

![]()

Feel free to comment with any questions or thoughts; you can also contact me directly at strengthscrolls@gmail.com

Thanks for reading!